Thresholds, Not Pictures: Art’s Quiet Return to the Sacred

This essay reflects on the enduring relationship between art, attention, and the human search for meaning, considering how painting may function as a site of encounter rather than description.

‘The sacred does not vanish,’ Simone Weil once suggested, “it is we who cease to look in the right direction.’¹

As a visual artist, I have taken this less as a theological claim than a phenomenological one. Weil is not trying to reassert the divine; she is describing a shift in human perception. Something narrows. Something in us forgets how to attend. Yet the world, in all its depth and strangeness, continues unperturbed. When I think about what art does at its most profound level—when a work slows me, troubles me, or draws some half-recognised awareness into focus—I find Weil’s line returning like a refrain. It is possible that art is one of the ways we relearn how to look.

This raises an older question: What makes certain works of art feel profound? Why do they seem to contain or generate more than the marks and materials before us? And how has that sensation endured across cultures whose beliefs, rituals, and metaphysics have shifted radically? The popular historical narrative, which tells of a clean break between art and faith—one drifting toward secular aesthetics, the other toward institutional doctrine—never fully aligns with what happens in the actual encounter. Stand before a work that exerts pressure, that opens a perceptual depth, that feels addressed rather than simply made, and the neat boundaries between sacred and secular falter.

This suggests that the impulses behind art and the impulses behind faith might be two expressions of the same human orientation toward meaning—a readiness to meet the world as something capable of revealing itself.

This is not speculative romanticism. The evidence is carved into the earliest art we possess. In Lascaux, animals twist and surge across limestone with a vitality that defies our categories of depiction or record. The cave wall behaves like a membrane; the images seem coaxed from the stone itself. There is no strict separation here between image and ritual, between gesture and invocation. These paintings participate in the world rather than describe it. They do what ritual does: they acknowledge that the world is more than what it provides to the senses.

Nietzsche, writing millennia later in a wholly different idiom, names something similar when he claims that ‘we have art in order not to perish from the truth.’² The truth he invokes is not factual but existential: the frightening density of being, the unmanageable intensity of the world. Art, for Nietzsche, is a mediator. It enables the encounter without letting us be overwhelmed. Whether he intended it or not, the cave painter and the modern abstractionist share this recognition: to make is to negotiate with the intensity of existence.

The medieval world framed this same human capacity through theology. The illuminator preparing a gospel is not enhancing text; they are constructing a locus of presence. Gold leaf does not imitate radiance but enacts it. Ultramarine, ground from lapis brought from Afghanistan at immense cost, signals a cosmology in which certain materials bear inherent dignity. The page becomes a threshold through which the sacred might appear. Art, here, is an act of attentiveness bordering on devotion.

Holman Hunt, working in an age that considered itself rational and empiricist, nonetheless held fast to this older intuition. Reflecting on The Light of the World, he admitted he had painted ‘not the Christ I saw, but the Christ I felt.’³ The distinction is not rhetorical. It demonstrates a belief that art discloses rather than copies, that the image is a site of encounter rather than illustration. Even without sharing Hunt’s theology, one can recognise the metaphysics: the conviction that matter can bear moral intensity, that pigment and light can become thresholds for recognition.

Vasari’s exuberance, though often lacking restraint, preserves a similar insight in his description of Fra Angelico painting ‘not through art, but through faith.’⁴ This is not a denial of technique; it is an affirmation that technical action can be a form of attentiveness, a way of preparing oneself for what might appear through the process.

Oscar Wilde, circling the question from a largely secular vantage, gestures toward the same structure when he writes in the preface to Dorian Gray that ‘All art is quite useless.’⁵ He does not mean that art lacks value, but rather that its value lies precisely in its refusal of utility—its arrival as revelation rather than instrument.

Across Wilde, Vasari, Hunt, Weil, and Nietzsche, a strange and cohesive theme emerges: art becomes most itself not when it explains, but when it opens; not when it instructs, but when it discloses; not when it asserts, but when it allows the world to reveal more than intention can contain.

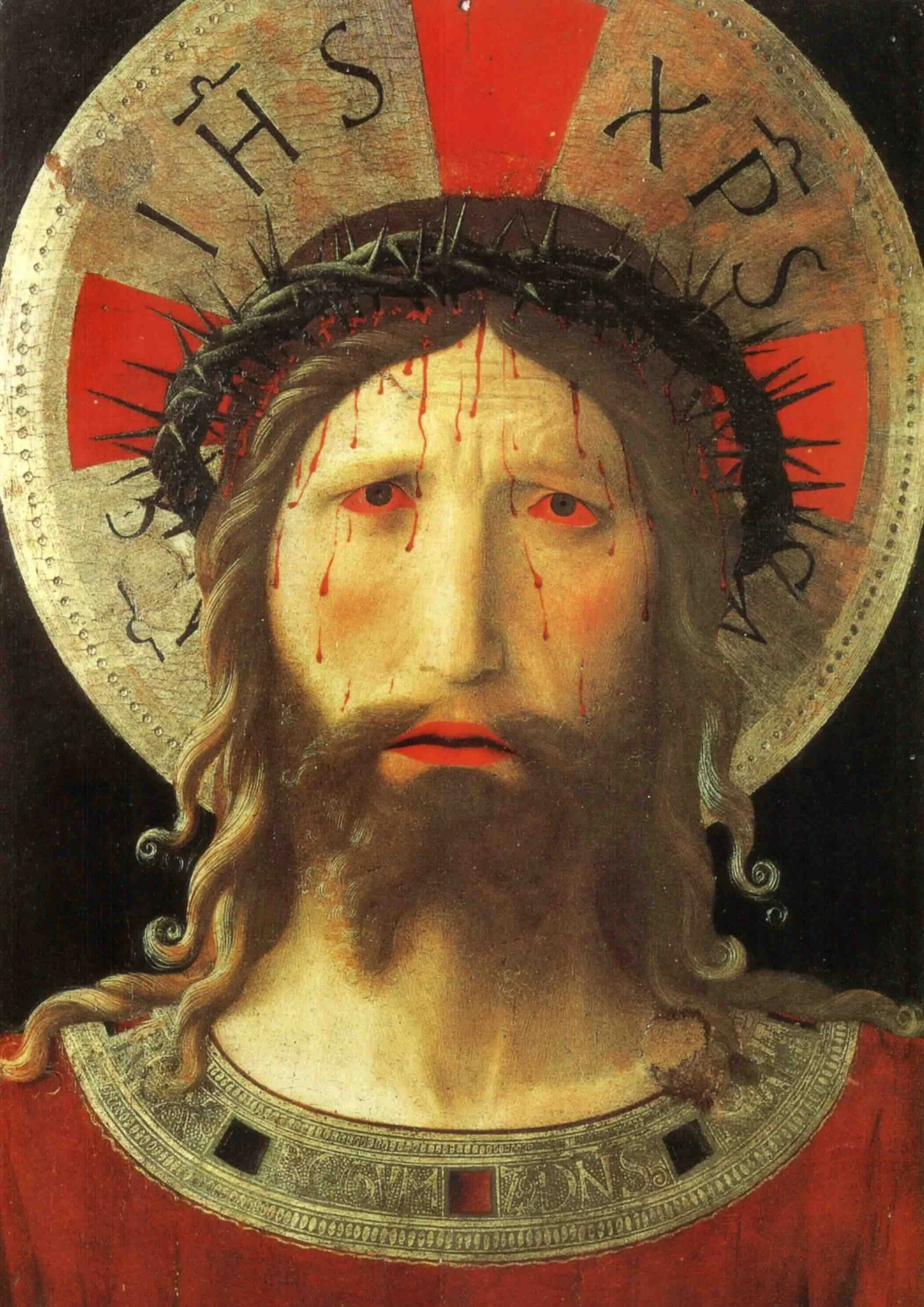

Fra Angelco. Christ Crowned with Thorns. c. 1438.

According to Vasari, Angelico believed that painters of sacred images ‘must be united to God.’ He made art as a form of attentiveness, not performance.

The Enlightenment attempted to sever this lineage. Under the auspices of clarity and mastery, matter was recast as mechanism: inert, predictable, self-contained. Art, in turn, was asked to imitate the visible or express the subjective. Both assumptions diminish the role of the world. Representation demands fidelity to the already-known; expression demands fidelity to the interior self. In both cases, the world’s agency is stripped away. This is the philosophical flattening that ruptures the participatory thread running from Lascaux to the scriptorium and from the Quattrocento workshop into the early modern studio.

Yet artists, almost without exception, resisted the flattening. Turner discovered atmospheres in pigment that eluded contemporary scientific explanation. His late works dissolve form into light in ways that feel less like representation and more like mysticism : the sky becoming numinous not meterological . Cézanne realised that perception itself is instability in motion’the motif,’ he duggestred in his letters, ‘achieves me.’⁶ Kandinsky heard colour as vibration, as inner pressure, claiming that certain hues ‘set the soul vibrating.’ Modernism, for all its rhetoric of rupture, becomes the great rediscovery of the world’s liveliness. It is as if the supposedly disenchanted age found itself surrounded by behaviours it could not rationalise.

Nietzsche’s famous declaration that ‘God is dead’ is often misread as a celebration of secular liberation. In fact, Nietzsche is offering a eulogy for the collapse of shared metaphysical structures. Meaning, in the nineteenth century, is no longer collectively inherited. It must be forged through encounter. Art becomes one of the primary sites where this new work occurs: not by reaffirming religious imagery, but by enabling perception to recover its depth.

This is why modern art feels religious without being doctrinal. It retains the structure of devotional attention while shedding its historical forms.

It is here that Bertrand Russell enters the conversation from a surprising angle. Russell, committed to clarity and verification, famously proposed the analogy of a celestial teapot orbiting the sun—a hypothetical object whose undisinprovability, he argued, renders it meaningless.⁷ For Russell, claims that cannot be verified are empty. In theology, this may be a useful provocation. In art, it collapses immediately. A painting’s presence—its atmosphere, its internal pressure, its capacity to alter mood, expectation, or orientation—cannot be proved, and yet it is experientially incontrovertible. The absence of empirical verification is not a failing; it is the condition under which artistic truth becomes possible. In art, the unverifiable is often the most real.

Science asks for verification. Art and Faith don’t ignore evidence—they simply seek it elsewhere. Their truths arrive through encounter, not experiment.

This is precisely where art and faith touch again. Faith, in its earliest and widest sense, is not assent without evidence; it is a mode of evidence, an experience of the world that arrives through encounter. John Milbank describes this structure theologically as sacramentality: the conviction that the world is more than itself because it participates in a deeper givenness.⁸ Johnny Golding, speaking from a radically different metaphysical standpoint, describes an almost identical structure in the language of radical immanence: matter unfolding as event, generating intensities from within rather than waiting for meaning to descend upon it.⁹ One framework bends toward theology, the other toward posthuman materialism, yet both recognise that the world reveals itself through behaviour, not explanation.

This helps explain why contemporary art so often appears closer in spirit to ancient art than to nineteenth-century naturalism. Pollock’s poured lines behave like liquids under tension; his surfaces are arenas where viscosity, gravity, and momentum collide. Rothko’s colour fields hover in a state of trembling dusk, neither symbolic nor descriptive, yet saturated with presence. Barnett Newman’s vertical “zips” divide space with an austerity that feels architectural, almost liturgical. These works do not depict. They enact. They create conditions under which the world may appear as event.

The philosophical vocabulary we inherit turns out to be unexpectedly convergent. Milbank’s sacramentality, Golding’s eventfulness, Nietzsche’s existential intensity, Wilde’s aesthetic faith, Hunt’s moral luminosity—all attempt to describe the same structure: the world breaks open. Something appears that cannot be reduced to representation or concept. Something resists our categories and yet insists upon being felt.

It is within this continuum that I locate my own practice. The paintings I make begin with grounds built from particulate matter—chalk, limestone dust, powdered pigments—materials chosen for their capacity to behave rather than obey. Over these, I work stains, erasures, abrasions, atmospheric veils. The surfaces do not act like neutral containers. They respond. They suggest. They push back. They carry a residue of geological memory, as though the world were remembering itself through the making.

Occasionally, luminosity emerges—not as something I impose, but as something disclosed by the material in the process of its own unfolding. I do not treat this as mysticism. I treat it as evidence of encounter: the studio as a site where matter thinks with us, where making becomes a negotiation rather than an imposition, and where meaning arises through exchange.

When viewers describe a sensation of arrival—as if something tenuous but insistent is surfacing—I recognise the structure immediately. The painting is functioning as a threshold, not a picture.

This sense of the painting as threshold is not unique to my studio; it is part of a much longer history in which art serves as a site where the world’s depth becomes perceptible. From the glow of an icon panel to the dissolving atmospheres of Turner, from the carved density of Michelangelo’s unfinished slaves to the soft radiance of a Rothko chapel canvas, the underlying gesture is recognisably constant: art does not merely show the world—it invites the world to show itself.

Simone Weil’s remark becomes particularly resonant here. If the sacred does not vanish but waits for us to look in the right direction, then art becomes a training in that direction. It is neither religious in a confessional sense nor secular in the reductive sense. Instead, art becomes a mode of attention that cuts across these distinctions. It teaches a kind of perceptual hospitality—an openness to the possibility that meaning may arrive unbidden.

This helps explain why the supposed divide between art and faith is, in practice, less decisive than the textbooks claim. Historically, of course, art has been used to affirm belief, to tell stories, to illustrate doctrine. But this instrumental dimension never fully contains the deeper phenomenon: the capacity of an image to change the quality of attention. Faith in its richest sense is not reducible to belief; it is a way of attending to the world as if depth were possible. Art, when it succeeds, cultivates precisely this stance.

This is especially evident in periods of transition, when older metaphysical frameworks are collapsing. The Renaissance, for example, is often described as the triumph of humanism, yet the work of Fra Angelico, Michelangelo, and even early Titian reveals less an abandonment of the sacred than a shift in its locus. Light moves from halo to atmosphere; divinity moves from gold leaf to flesh. Faith does not disappear; it migrates into new forms.

The same is true of modernism. Far from being a purely secular revolt, it often reads as a search for new modes of transcendence after the collapse of older certainties. Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art is explicit on this point: abstraction, for him, is a way of accessing the ‘inner necessity’ of forms. Newman’s claim that ‘the impulse of modern art is the desire to destroy beauty’ is less nihilistic than it sounds; he is perhaps attempting to clear the ground for a new kind of presence, one that does not depend on inherited symbols.

This migration of faith into artistic practice becomes even more evident in the late twentieth century, when the dominant cultural narrative insists upon secular disenchantment. Yet artists continue to experience materials as alive, as resistant, as capable of revealing unexpected intensities. The world refuses to flatten. Dust, resin, soil, ash, air, liquid, metal—these substances behave in ways that exceed intention. Even conceptual art, in its best moments, acknowledges this unpredictability: repetition, erasure, and duration become rituals through which meaning unfolds over time.

Thus, even in a secular age, the structure of encounter persists. The world continues to press forward. And art continues to provide spaces where that pressure can be felt, interpreted, or at the very least acknowledged.

In this light, contemporary art—often characterised as secular, ironic, or conceptually detached—begins to look very different. The deeper one moves into the practices of painters, sculptors, installation artists, and even time-based practitioners, the clearer it becomes that a residual, perhaps irreducible, attentiveness survives beneath the surface rhetoric. Artists speak of waiting for a work to ‘settle,’ for a surface to ‘resolve,’ for a form to ‘reveal’ itself. These phrases are not mystical indulgences; they are phenomenological accounts of material encounter.

What these practitioners articulate, often intuitively, aligns with what Milbank frames theologically and what Golding frames materially: truth emerges in the meeting between self and world. It is not imposed by the artist nor located solely in the object. Instead, it arises through the dynamic interplay of intention, resistance, accident, and recognition. Art, in this sense, does not merely depict or comment; it participates.

And participation has theological resonance. The medieval theologians understood sacrament not as magic but as relational ontology: matter becomes a site where the divine is encountered because the world is saturated with givenness. Contemporary artists, perhaps unknowingly, mirror this stance when they treat materials as active agents rather than inert carriers of concept. The dust that drifts into a layer of medium, the way oil sinks into an unprimed linen, the unpredictable pooling of a solvent—these events testify to a world that behaves.

This is why so much contemporary art feels strangely ancient. A work built from soil or ash resonates with the same material humility as a prehistoric pot or a votive figurine. A painting that trades depiction for atmospheric presence calls back to the glow of Byzantine gold. A sculpture that leans, folds, or collapses under its own weight reminds us of the shared vulnerability of body and matter. Even digital art—when it succeeds—finds ways to produce events rather than images, disruptions rather than representations.

Ali Cherri. Work from How I Am Monument. Mud, straw and junk shop finds, Baltic Centre For Contemporary Art , Gateshead. 2025. A show which explored the monumental in Art .

This continuity does not imply that contemporary art is covertly religious. Rather, it suggests that art and faith share a fundamental orientation toward the world. Both practices arise from the intuition that reality is not exhausted by surface appearance. Both cultivate the kind of attention that lets meaning emerge rather than be forced. Both acknowledge that the world has depths that cannot be grasped by concept alone.

It is in the studio where this becomes most palpable. I recognise it in my own work: the moment when a layer of particulate ground catches light in an unexpected way; the moment when a scraped-back surface reveals a palimpsest of earlier decisions; the moment when the painting seems to lean toward a state I did not foresee. These are absolutely not instances of inspiration descending from above. They are moments of negotiation in which the material asserts its own logic.

When viewers speak of feeling something ‘arrive’ in these works, I do not dismiss the comment as metaphor. It signals a small but significant truth: the painting has become a threshold. It is functioning less as a picture than as an event. And in that event, maker and viewer alike encounter the world behaving—slowly, quietly, sometimes insistently.

This kind of encounter, historically associated with the divine, need not be tied to doctrine. It flourishes wherever attention deepens.

If there is a single thread that runs through the history of art—from the ochre animals of Lascaux to the gilded manuscripts of medieval Europe, from the carved gravitas of Michelangelo to the dissolving atmospheres of Turner, from Holman Hunt’s moral luminosity to the trembling dusk-fields of Rothko—it is the persistence of this deep attentiveness. Styles change, vocabularies fracture, metaphysics rise and fall, but the underlying gesture remains recognisable. Art, at its most alive, does not close the world down; it opens it. It becomes a space in which presence is not merely seen but felt.

This continuity resists the narrative that art and faith parted ways cleanly in the modern era. Faith, understood narrowly as assent to doctrinal propositions, did indeed struggle in a secularising world. But faith understood as a mode of perception—as attentiveness to depth, as expectation of encounter, as a readiness for disclosure—proved remarkably persistent. In many ways, this perceptual stance migrated into artistic practice. Faith, in other words, found the form suited to its age.

Consider the changing locations of revelation across history. In early societies, revelation often occurs through ritual image-making—Lascaux’s walls as porous membranes between the human and the unseen. In the medieval world, revelation becomes text and illumination: the page as a radiant threshold. In the Renaissance, revelation shifts into flesh and stone: beauty as theophany, the body as bearer of proportion and grace. In modernism, revelation detaches from representation and emerges through colour, rhythm, and abstraction: Newman’s “zip” offering a new kind of openness, Rothko’s rectangles offering a new kind of dusk.

In each case, the locus of revelation changes, but the structure persists. Something appears that cannot be reduced to technique or concept. Something opens that cannot be captured by language alone. The world arrives differently. This ‘arrival’ is what I experience in the studio when a painting moves beyond my intention and begins to behave with its own logic. It is what viewers describe when they sense atmosphere rather than image, presence rather than subject. It is the moment when art reveals its deepest affinity with faith: not belief, but encounter.

Simone Weil’s insight returns here with renewed force.

If the sacred does not vanish, then its disappearance from public discourse does not constitute its extinction—only the erosion of our capacity to see it.

And if art continues to cultivate the perceptual openness that Weil identifies, then art may well be one of the last widely available practices that trains us in this mode of seeing.

This does not render contemporary art religious in a traditional sense. Many artists working today are not interested in theology, and many viewers encounter works without any metaphysical expectation. Yet the phenomenology of the encounter—the sense that something appears, something arrives, something discloses itself—persists regardless of belief.

In this sense, contemporary art may be far closer to the divine than our secular categories allow. Not because it returns to traditional iconography, but because it preserves the stance that made such iconography possible: the expectation that the world contains more than its surfaces reveal.

As I reflect on how faith finds the form suited to its age, I cannot help but wonder whether, in our own, art has become one of the last shared spaces where revelation—in whatever transformed, secularised, or reconfigured guise—can still take place. And if this is true, or even partly true, then a final question presses forward: Is contemporary art closer to the divine than we, in our secular age, are prepared to suppose?

Notes

¹ Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace (London: Routledge, 1952).

² Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage, 1967), §822.

³ William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, vol. I (London: Macmillan, 1905).

⁴ Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, trans. Bondanella (Oxford: OUP, 1991).

⁵ Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, preface (London: Ward, Lock, 1891).

⁶ Paul Cézanne in Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991).

⁷ Bertrand Russell, “Is There a God?”, Illustrated Magazine (1952).

⁸ John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory: Beyond Secular Reason (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990).

⁹ Johnny Golding, On Radical Matter (London: RCA Publications, 2018).