Appropriation, Creative Iteration, and the Long Echo of Images

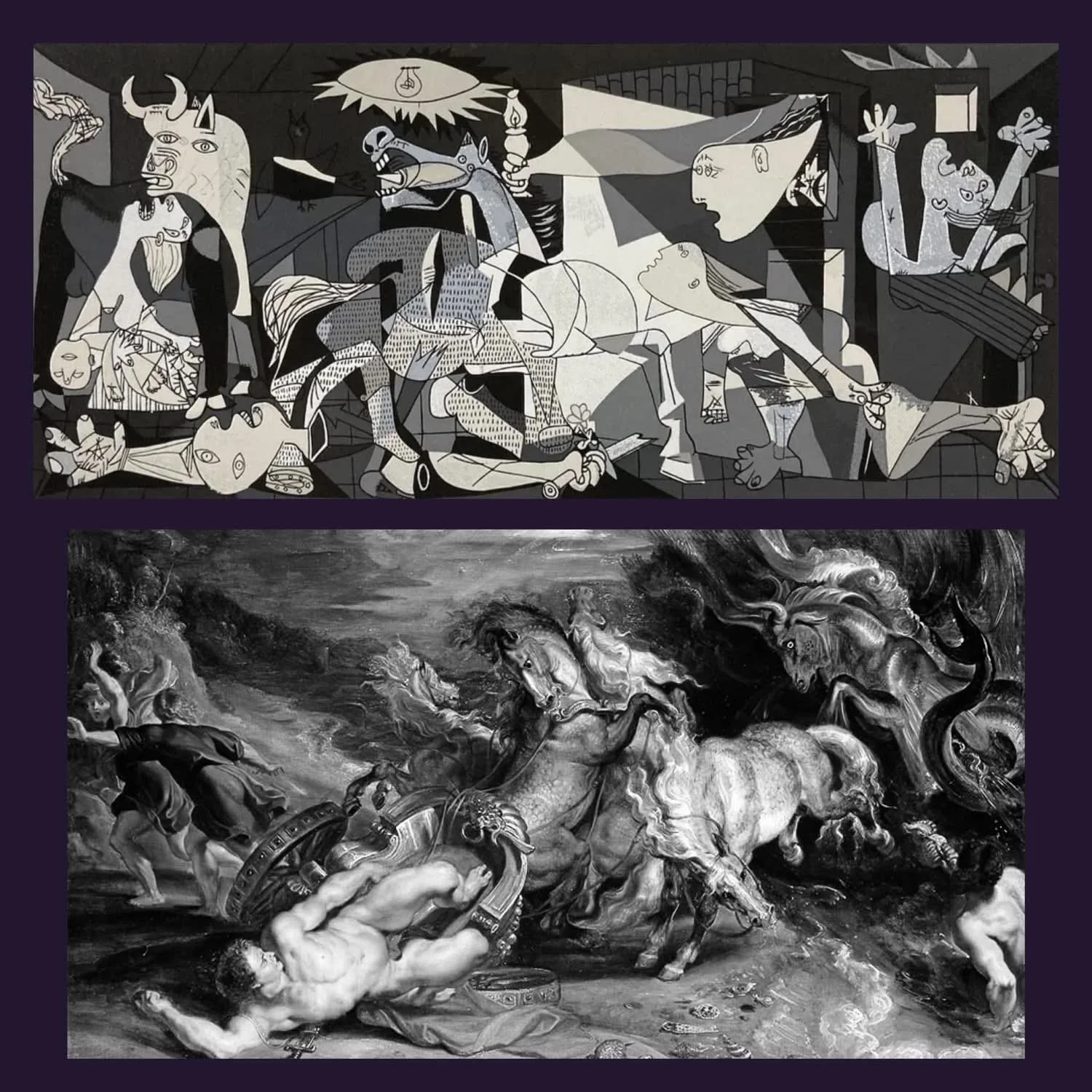

Guernica, The Death of Hippolytus, and the Productive Afterlife of Forms

Peter Paul Rubens’s Death of Hippolytus (1613). Artists do not inherit images; they inherit problems, and the structures devised to meet them, visual languages evolve by absorbing what came before.

Appropriation in art is often framed as a modern anxiety: a question of ethics, originality, and even intellectual property. Yet when seen historically it is far closer to a principle of creative iteration, the idea that images may be retained in canonical form, as in Byzantine iconography, or else carried forward, mutated, and reactivated across time in response to new cultural demands. Rather than theft, iteration appears as an unavoidable and even necessary mode of thinking: a means by which artists metabolise earlier forms in order to speak more forcefully within their own historical moment.

As a practising painter, I would suggest that artists do not simply inherit images. They inherit problems, and the structures devised to meet them. Visual languages evolve not through invention ex nihilo but through the appropriation and transformation of existing solutions. This is what Picasso himself implied when he explicitly rejected linear chronology in art, insisting that ‘there is no past or future in art’, and that a work matters only insofar as it continues to act within the present. Art, in this sense, does not progress forward so much as it circulates, reorganising its own internal memory.

A particularly charged example lies in a comparison that art historians have occasionally noted but rarely pursued: the compositional resonance between Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and Peter Paul Rubens’s The Death of Hippolytus(c.1611–1613), now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Rubens’s painting is a spectacular convulsion of bodies, hooves, and ruptured narrative: a conflation of myth, erotic tension, violent rupture, and divine intervention. The canvas reads as an explosion, not of light, but of bodies subjected to forces beyond their control.

Guernica is a different kind of explosion: political, modern, and evacuated of colour. Yet both works operate through a grammar of dislocation. Figures are flung out of narrative continuity, limbs splay outward from implied shocks, and the scene is driven by a centripetal violence that draws the viewer into its turbulence.

While no published record confirms that Picasso ever saw Rubens’s painting in Cambridge, it remains historically plausible that he encountered Richard Earlom’s late-eighteenth-century mezzotint after Rubens, executed in 1796 and published in London in 1797. The engraving circulated widely within Europe’s reproductive print economy and is documented in French national collections, including verified impressions in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, where British mezzotints after Old Master paintings formed part of both institutional holdings and academic visual culture. Within this context, Earlom’s monochrome translation of Rubens would have been fully accessible within the Parisian artistic milieu in which Picasso was immersed. Its tonal reduction echoes Picasso’s own choice of monochrome for Guernica, (widely interpreted as evoking the stark immediacy of news photography, reportage, and documentary evidence).

The compelling point here is not the romantic idea of influence but the more practical one of visual problem-solving. Both artists confronted the challenge of depicting catastrophic, multi-figure action while preserving legibility and emotional concentration. Rubens resolves this through a sweeping diagonal composition that draws the collapsing horses and the doomed Hippolytus into a vortex of divine retribution. Picasso fractures the problem apart through modernist disjunction, replacing narrative continuity with interlocking planes and spatial collapse. Yet the underlying task, how to orchestrate chaos, remains compellingly shared.

It is here that appropriation becomes iteration: the selective re-use of compositional tools, emotional armatures, and pictorial strategies. Art history unfolds as a chain of such transformations. Rubens absorbs antiquity; Picasso absorbs Rubens; contemporary artists absorb both. What passes between them is not quotation or pastiche, but a repertoire of structural solutions. Artists do not simply inherit images; they inherit visual problems and the compositional architectures devised to resolve them.

The possibility that Picasso encountered Earlom’s mezzotint thus functions less as a claim of direct borrowing than as evidence of a broader condition: artists draw upon the visual archive available to them, consciously and unconsciously. Stripped of colour, Rubens’s composition becomes a matrix of tonal contrasts, directional forces, and collisions of mass, precisely the tools Picasso deploys to organise Guernica’s fractured, discordant space.

There is also a deeper ontological affinity. Rubens’s painting stages the catastrophic consequences of divine desire. Guernica, by contrast, renders the consequences of political desire: fascism’s appetite for domination, mechanised from the air. Both works insist that violence does not occur in a vacuum; it erupts from structures of power, mythology, ideology, and belief. Their continuity is not merely visual but ethical: in each, the protagonists are overwhelmed by Deus Ex Machina like forces which exceed human agency.

Creative iteration, viewed this way, is less a matter of origin than of continuity. It shows how visual languages evolve by absorbing what came before, transposing inherited forms into new ethical, political, and perceptual registers. Artists draw on images they have seen, half-remembered, misunderstood, or absorbed atmospherically through cultural circulation. Influence is rarely a straight line, nut more akin to a field of overlapping forces.

In linking Guernica and The Death of Hippolytus, we see not derivation but conversation. Rubens provides a vocabulary for depicting bodies under duress; Picasso redeploys that vocabulary to describe a modernity tearing itself apart. The act is not appropriation in the adversarial sense, but iteration: a creative re-use of the deep structures of pictorial thought. Great images are not isolated peaks but strata in a long, interconnected terrain where forms move, transform, and reappear when needed most.

If Rubens and Picasso exemplify the productive afterlife of images, the twentieth century also offers examples of artists who attempted the opposite: the pursuit of an image that refuses lineage altogether. Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square(1915) is often treated as the canonical declaration of creative zero. Malevich positioned it as the ‘zero of form’, a radical attempt to sever ties with representation, narrative, and inherited pictorial language. In its stark geometry and refusal of reference, the Black Square stands as one of the boldest attempts at non-iteration, an image that seeks to unhook itself from the accumulated freight of cultural memory.

Similarly, Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals (1958–59) have been widely interpreted as a retreat from historical figuration and quotation, striving instead for a direct, immersive encounter with colour, scale, and affect. Rothko sought to envelop rather than describe, confront rather than narrate. The murals propose painting as an experiential environment rather than a pictorial record.

Yet neither Malevich nor Rothko escapes the gravitational field of earlier images. Our visual consciousness is deeply embedded in long cultural memory. Even images designed as ruptures rapidly become absorbed into lineage. The Black Square reads, in practice, as a culmination of iconographic reduction rather than a creation ex nihilo, invoking religious icons, voids, tombstones, and cosmological diagrams. Rothko’s floating fields recall Turner’s atmospheric dissolution, the solemn frontality of Byzantine art, and the architectural gravity of monumental mural traditions.

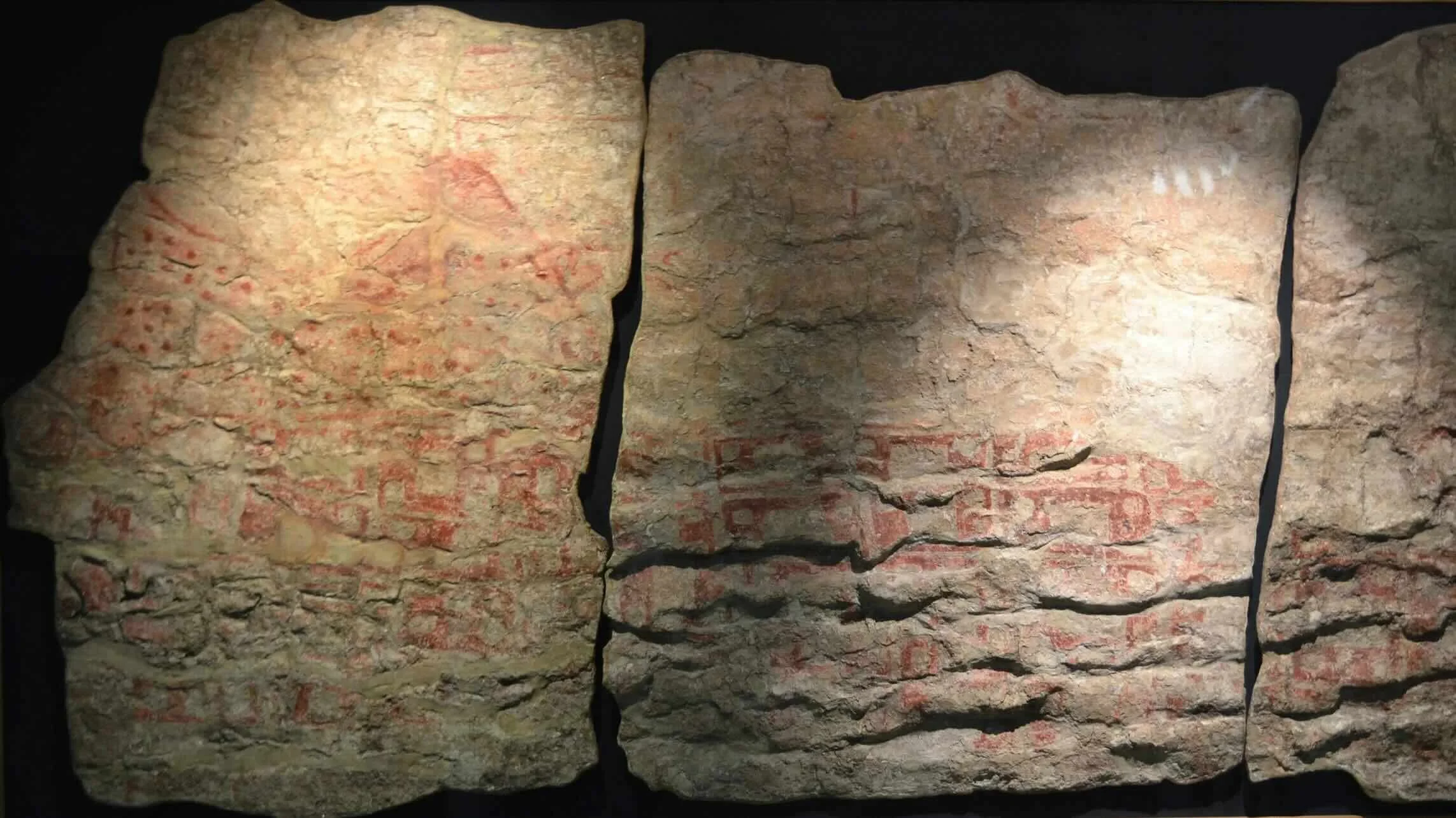

As Picasso observed, there is no creatiely meaningful chronology in art. Çatalhöyük’s Neolithic ‘volcano’ paintings, though separated from him, and us, by millennia, uncannily evoke modernist abstraction. Images cannot avoid evoking other images.

Çatalhöyük’s Neolithic ‘volcano’ paintings echo the abstract work of Christopher Le Brun PRA.

This is not a failure of originality but a condition of image-making. Newness is never hermetic. It must pass through the viewer’s memory, layered with centuries of visual habit. An image cannot avoid evoking other images because viewers cannot avoid forming those connections. Our eyes have been trained, by museums, books, screens, and cultural inheritance, to read form relationally.

Which brings us back to the problem of iteration. If every image inevitably participates in a wider visual ancestry, then iteration is not merely a strategy; it is a fact. Artists may attempt to escape history, but viewers never do. A painting exists within a web of recollection, inference, and recognition. Iteration, whether conscious or resisted, is unavoidable.

To lean into this is not to surrender originality but to locate where originality actually resides. It lies not in severing ties with the past but in recombining inherited forms, problems, and emotional architectures into new experiential configurations. Picasso does not diminish himself by echoing Rubens; Rothko does not collapse by echoing Turner; even Malevich, despite proclamations of transcendence, inhabits a lineage of radical reduction from Byzantine icon to Cubist fracture.

If iteration is the shared condition of both human art and AI production, then the difference between them must be found not in whether they repeat, but in how they repeat. Here a Deleuzian framework becomes decisive. For Deleuze, repetition is never simple recurrence; it generates difference, producing singularity rather than sameness. What appears as repetition becomes, in practice, transformation.

Under this lens, the danger of AI image-generation lies in repetition without difference: recombination without experiential novelty. The machine rearranges visual patterns extracted from vast image corpora, but it does not undergo the embodied, affective, and material negotiations through which genuine difference emerges in human making. It does not encounter resistance, hesitation, risk, or failure. It does not confront the obstinacy of matter, the instability of intention, or the temporal drag of decision. Instead, it operates through probabilistic optimisation, selecting statistically plausible visual outcomes rather than wrestling form into being through lived engagement.

In human artistic practice, repetition is never merely formal. It is inflected by physical fatigue, emotional fluctuation, technical limitation, cultural memory, and situational contingency. Each iteration is pressured by circumstance, shaped by error, and re-routed by discovery. Difference does not arise from novelty of form alone, but from the accumulation of situated decisions, material negotiations, and perceptual recalibrations that occur during prolonged acts of making. In this sense, repetition becomes productive precisely because it is unstable, extended, and exposed to interruption, vulnerability, and chance.

AI, by contrast, does not inhabit conceptual or perceptual time in this way. Its operations are reversible, instantaneous, and consequence-free. It does not learn through embodied adaptation, nor does it risk irreversible commitment. There is no sedimentation of experience, no material memory, no psychic residue carried forward into subsequent acts of production. Each output is statistically coherent yet existentially weightless. While AI can generate endless variation, it cannot generate artistic transformation. Its differences remain parametric rather than ontological.

This distinction explains why AI repetition remains bound to resemblance rather than lived transformation. The machine can remix surface features but cannot reorganise the perceptual conditions from which images arise. It produces images that look different without being different in the Deleuzian sense. What is missing is not originality but encounter: the collision between intention and resistance, between desire and material limit, through which form is forced to become other than it first appeared.

AI outputs thus remain locked within an economy of recognition. They confirm expectation, satisfy stylistic prediction, and reinforce established visual grammars. Human making, by contrast, continually destabilises its own procedures. It generates difference not by escaping precedent, but by failing to repeat it cleanly. Each misalignment, hesitation, or resistance introduces new possibilities into the perceptual field. It is precisely this friction, this refusal of seamless replication, that allows art to evolve rather than merely circulate.

Prof. Johnny Golding’s distinction between thin seeing and thick seeing clarifies this divide. Thin seeing operates through surface recognition and pattern extraction, the domain in which AI excels. Thick seeing, by contrast, arises when perception is inflected by embodied labour, material resistance, and existential decision. Thick seeing is not recognition but encounter.

Human artists, even when unconsciously iterating inherited forms, produce thick repetitions: repetitions that generate new perceptual conditions, emotional intensities, and modes of address. AI, lacking agency, intention, and material engagement, cannot convert repetition into difference in the Deleuzian sense; it can only circulate resemblance.

This clarifies what remains vital in art after the myths of originality collapse. Iteration is universal, but only human iteration becomes agency: an agency of materiality, perception, and concept that is experiential, embodied, and transformative. It is this thick terrain of making and meeting, rather than surface novelty, that sustains art’s capacity to generate meaning.

Creative iteration thus becomes a way of thinking through art history without being confined by it. It acknowledges that images are porous and viewers historically saturated. Rather than fleeing that condition, artists exploit it, bending inherited structures into new ethical, political, and emotional registers. Iteration is not the enemy of innovation but its essential raw material.

In this sense, the most genuinely new works are not those that sever the web, but those that tug at its strands in unexpected directions: Rubens to Picasso, icons to Malevich, Turner to Rothko. Each reminds us that images survive by becoming other versions of themselves, and that every artist joins the long chain of those transformations.

Selected Sources

Picasso on art & time

Picasso, ‘Picasso Speaks’, interview with Marius de Zayas, The Arts, May 1923; repr. in Dore Ashton (ed.), Picasso on Art, Thames & Hudson, 1972.Iteration, perception, and historical seeing

E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion, Phaidon, 1960.Difference, repetition, and becoming

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, Columbia University Press, 1994.

Thick seeing is not visual recognition but perceptual encounter