Porosity: When Paint and Viewer Meet

A porous painting is one that does not close down meaning but invites entry. (work by Joan Mitchell).

If granularity describes the smallest thresholds of facture and agency describes the negotiation between painter, material, and beholder, then porosity describes the openness of painting to the world beyond itself. A porous painting is one that does not close down meaning but invites entry. Its surfaces leak into perception, allowing viewers to see not only what is pictured but what might be imagined. Porosity names the way painting remains unfinished in the eye of the beholder, open to interpretation, to projection, and to time.

This idea is central to my developing doctoral research project, Granularity, Agency, and the Pedagogy of Becoming, which asks how painting’s material thresholds can be understood as ontological as well as pedagogical. Porosity is crucial here because it describes not only a condition of works of art but also a condition of learning. My time at the Royal College of Art, where I developed the series The Entropic Pull of Matter over Memory, made this clear in practice. Those works emerged from the decision to treat surfaces not as resolved images but as unstable sites, layered with chalk, limestone dust, and recycled detritus. They are paintings that breathe ambiguity: surfaces on which pareidolic forms emerge, suggesting bodies, landscapes, or ruins, only to dissolve again into pure material. They resist the viewer’s attempt to fix them, offering recognition but withholding certainty. In this way they embody porosity: the unfinished edge where meaning opens and escapes.

This use of porous surface has deep precedent in art history. In Rembrandt’s late portraits, loosely handled passages of paint seem to dissolve into shadow, only to cohere again as the viewer steps back. These porous zones allow viewers to enter, to complete the work in perception. The Impressionists, in their different ways, extended this openness: Monet’s dissolving cathedrals or Renoir’s flickering figures are less about solidity than about atmosphere, a permeability between object and light. Cézanne, often described as the hinge between Impressionism and modernism, built porosity into structure: his tilted planes and shifting contours never quite resolve, keeping the viewer suspended in process. Modernism’s experiments with form and perception carried this principle forward: Cubism fractured objects into facets not in order to close them down, but to allow multiple readings to remain active at once.

For me, these histories became most vivid not in theory but in the entropic surfaces of my RCA work. Matter was allowed to assert itself: pigment bled into absorbent grounds, mineral dust created a resistant drag, oil pooled and broke. Each material intervention carried with it an invitation to pareidolia. The viewer might glimpse a figure emerging in a stain, or a landscape forming in a striation of chalk, but as quickly as it appeared, it resisted capture. This was the point: porosity in these works lies in their refusal to resolve into single meaning. They operate in what I call the entropic register of painting, where matter pulls against memory, and where perception is always provisional.

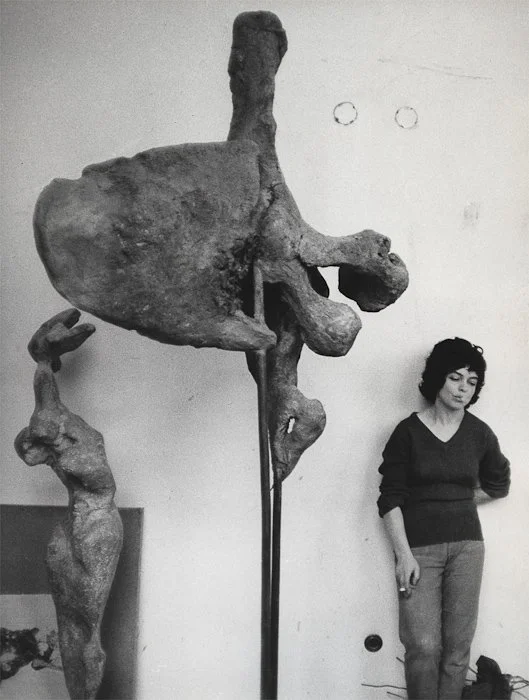

Porosity is not confined to painting. Abstract work depends upon it as well. Pollock’s all-over fields resist singular focus, allowing viewers to move across them endlessly. Joan Mitchell’s canvases invite a similar openness: strokes lead the eye in multiple directions, never stabilising into a fixed reading. Mark Rothko’s colour fields, which at first seem sealed and monolithic, reveal themselves to be porous through layers of scumbling and glazing; colour breathes into the viewer, evoking not a single interpretation but a range of affective responses. Sculpture, too, finds its porousness. Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth cut literal holes into forms, opening the solid mass of bronze or stone to space, light, and sky. Alina Szapocznikow approached porosity differently, casting lips, breasts, and limbs in resin, latex, or polyurethane, often embedding them with light. Her works are porous not only in their physical materiality — translucent, fragile, fragmentary — but also in their meanings, leaking between the sensual and the abject, the intimate and the monumental. Where Moore and Hepworth created voids that connect figure to landscape, Szapocznikow created cavities and impressions that connect body to time, memory, and loss. Even architecture can be porous: Carlo Scarpa’s walls, perforated with apertures, invite light to play and shadow to move. In every case, porosity is the condition that prevents closure, that resists finality, that insists on relation.

Alina Szapocznikow, Dervish, 1969, bronze, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Cast in bronze yet marked by instability, Dervishtwists bodily form into a porous figure that both recalls and resists wholeness. Its surfaces fracture the line between sensual presence and material entropy. In my Entropic Pull of Matter over Memory series, porous facture achieves a similar effect: pareidolic images arise within chalk and oil yet remain unstable, resisting finality. Both Szapocznikow’s Dervish and my entropic works stage figuration as precarious and porous, a negotiation between memory, matter, and perception in contemporary practice.

Szapocznikow also demonstrates how porosity is never only formal but deeply tied to technē. To cast a mouth in resin, to embed it with a flicker of electric light, to accept the brittleness and impermanence of latex as a medium — these are not just acts of making but of deciding. They represent a choice for fragility over permanence, for openness over closure, for materials that will not last but will remain porous to time and entropy. Technē here is not simply the exercise of skill but the orchestration of meaning through decisions that accept instability. In this sense, Szapocznikow’s porous sculptures mirror the porous facture of The Entropic Pull of Matter over Memory. In both, surface is allowed to remain open, resistant, suggestive. Porosity becomes both a formal and philosophical stance: the work refuses finality, insisting that meaning is a negotiation between suggestion and resistance.

From a philosophical perspective, porosity resonates with Ernst Gombrich’s account of the “beholder’s share,” in which unfinished images draw the viewer into completion.¹ It aligns with Roland Barthes’ notion of the writerly text, where the reader participates in the act of meaning-making rather than passively receiving it.² In both my own work and that of these precedents, porosity is not simply a perceptual trick but an ontological stance: it accepts that meaning is never singular but always co-produced.

This stance has profound pedagogical implications. Students frequently strive for closure, believing that a painting must answer every question and resolve every edge. To leave ambiguity, they fear, is to reveal incompetence. Yet some of the most powerful works in history are precisely those that hold back, that allow space for the beholder. Teaching porosity means teaching restraint, encouraging students to see that to stop short is sometimes to say more. At the RCA, in my own work, I experienced the difficulty of this first-hand: resisting the impulse to resolve surfaces into image, allowing ambiguity to remain. In PRIMER, I now ask students to confront the same challenge, leaving passages unresolved, resisting their instinct to polish or explain. They discover, as I did, that when a work is too tight, it suffocates; when it is porous, it breathes.

Technē becomes indispensable here. Traditionally understood as skill or craft, technē has too often been reduced to the mechanical act of making. Yet in painting technē is also the act of deciding. To allow a ground to show through, to leave a mark ambiguous, to accept an accident rather than overpaint it: these are not only technical moves but epistemic decisions. A porous painting or sculpture does not arise from accident alone; it requires judgement. The artist must choose how porous to be, how much to give, and how much to withhold. In this way, technē is not simply manual but philosophical, a practice of discernment that balances openness with form. Every brushstroke, every cast, every aperture is both a technical operation and a decision about meaning.

Porosity also brings us back to the scopic regime described in the exhibition Slow Painting (2019).³ To look slowly at a painting is to recognise that it withholds as much as it reveals. Porosity conditions this regime, establishing the pace and depth of looking. A highly finished, closed painting dictates its meaning at a glance, leaving little room for variation. A porous painting slows the viewer down, forcing attention to hover, wander, and return. The scopic regime of porosity is one of openness, where vision is not consumed instantly but unfolded gradually, demanding patience and reciprocity.

In the context of contemporary culture, this matters deeply. The digital image presents itself as seamless, complete, frictionless. AI-generated images, polished to the point of implausibility, collapse ambiguity into instant readability. Against this, painting asserts its porousness. A painting resists the smooth finality of the screen; it insists on hesitation, on delay, on relation. Porosity reminds us that knowledge is not instantaneous but slow, not singular but plural. In an age where images threaten to be consumed without thought, the porous painting reintroduces resistance.

To think about painting in terms of porosity, then, is to see its openness as its strength. For art history, it reframes ambiguity as the very condition of vitality. For pedagogy, it teaches students to value withholding as much as finishing. For philosophy, it situates painting within debates on openness, relation, and becoming. And for my doctoral research, it completes the triad. Granularity locates meaning in the smallest units of facture, agency shows how those units negotiate between artist, material, and viewer, and porosity ensures that meaning remains open to the world. Technē is the hinge across all three: the way making is inseparable from deciding, the way technical actions are also epistemic choices. Porosity demonstrates that painting matters because it does not close down meaning but leaves it open, alive, and shared. The porous work reminds us that art, at its best, is not a finished statement but an ongoing conversation — between artist, material, beholder, and world.

References

Ernst Gombrich, Art & Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (London, 1960).

Roland Barthes, S/Z, trans. Richard Miller (New York, 1974).

Martin Herbert (ed.), Slow Painting (Hayward Gallery Touring, 2019).

Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA, 1985).

Isabelle Graw, The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium (Berlin, 2018).

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York, 1994).

Margaret Livingstone, Vision and Art: The Biology of Seeing (New York, 2002).